Teo-Jin and The Koi Spirit

This article is part of the Claritas spring 2025 issue, Connection. Read the full print release here.

by Max yap

Teo-jin sat on the bench and sullenly watched the twin suns descend lazily across the afternoon sky. With a mop of raven black hair, his ordinarily bright vermillion student’s tunic was marked brown with dirt, evidence of being thrown in the dust of the training courtyard an hour prior, defeated by the princess.

“Stupid Shae-Lun,” he muttered, thwacking his wooden sword at a neighboring ixora bush. “Daughter of the emperor and her cronies can go jump off a —”

“Treasonous thoughts, coming from the son of the emperor’s most trusted general,” interrupted a voice behind him.

Teo-jin sat up, his eyes darting across the imperial meditation gardens. “Who said that?” he challenged.

“Me.” Out of the willow that overlooked the bench dropped the court jester. Dusting off his hands, the jester affixed him with a bemused grin. Tall and lithe, with chestnut-brown hair and dark violet eyes, his unusually pale skin contrasted sharply with his simple black robe. “I simply couldn’t help eavesdropping on your brooding.”

“I didn't mean it like that, my father and I are loyal serv—”

“Oh relax, boy.” The jester waved a dismissive hand. “I know Princess Shae-Lun can be a real tool sometimes.”

Cautiously, Teo-jin sat back down on the bench. “Regardless, honored elder, I misspoke. I should not have voiced my opinions on the princess.” Not out loud anyway, he thought privately.

“Yet you still hold them.” The jester’s eyes glinted knowingly. The few times Teo-Jin had seen him at court, he had seemed like an amusing, boisterous fool. Now, shrouded beneath the dappled late afternoon light, his poised visage seemed more cunning. More thoughtful. Not malicious, but certainly not harmless either.

“I find the Orchid Empire’s system of rearing its young leaders fascinating,” the jester continued. “Training the children of your governors and generals together is supposed to help you develop bonds, not engage in brawls.”

Teojin thought back to the princess’s triumphant-looking face—beaming down at him after finally beating him at sparring. Sparring! The one area where he usually had the upper hand.

“I … can’t say you’re wrong,” Teo-jin sighed. “She’s just so … annoying! Mathematics, history, law—the two of us are always neck and neck!” The wood of his sword creaked under his grip. “The others practically trip over each other to praise her!”

“Sounds awful,” the jester said sarcastically. “Truly, I can never imagine another teenager who has ever had such an experience of ostracization.”

Teo-jin’s expression darkened. “I have better things to do than be your entertainment, fool.” He got up to leave when—

Snap.

Teo-Jin turned. In the shade of the willow, the jester guided a small, white flame between his thumb and forefinger. As he moved the flame through an arcane pattern, the flame left behind lines of light that hung like ropes stuck to pegs in an invisible wall, inscribed in a rough circle.

“What is that?” Teo-jin asked, transfixed, his annoyance momentarily forgotten.

“Magic,” the jester said, both hands continuing to weave the tapestry light, “of two varieties. A light and a story. Interested?” He fixed a serious look on Teo-jin.

“Yes,” he said, enraptured by the glowing lines.

“And so the story begins,” breathed the jester, twisting his wrists as the image before them rippled and darkened to reveal … a man lying on a road.

***

“There once was a man who was going down from the capital to his home, when he was attacked by robbers. They stripped him, beat him of his clothes, and left him for dead. Forlorn, he cried out to the gods for help—spirits powerful and capricious, as apt to inflict terrible curses as to dispense favor.

First came the Spirit of the Sky, a huge white stork who descended in a flash. The beating of his vast wings formed the storms and his keen eyes saw to the ends of the earth. Tempestuous clouds formed overhead as his gaze considered the beaten man.

“Please,” said the man. “Have mercy on me, great spirit.”

“No.” The stork replied, his voice filled with the icy howl of soaring winds. “I see your past, son of the earth. The heavens above are filled with light and have no mercy for the likes of you.” And just as suddenly, he lifted off, soaring into the sky.

Next came the Spirit of the Forests. Slinking out from the woods, a fox the size of a small house prowled before the man. Her hazel eyes were sharp and her ears twitched at the sounds of the forest around her. Kneeling beside the man, she sniffed him curiously.

“Please,” said the man. “Have mercy on me, great spirit.”

“No.” The fox replied. “I smell your nature, breaker of trust. The realm of the forest is mysterious, and you will lose yourself in its many paths.” The spirit slinked away, disappearing again into the shadows of the trees.

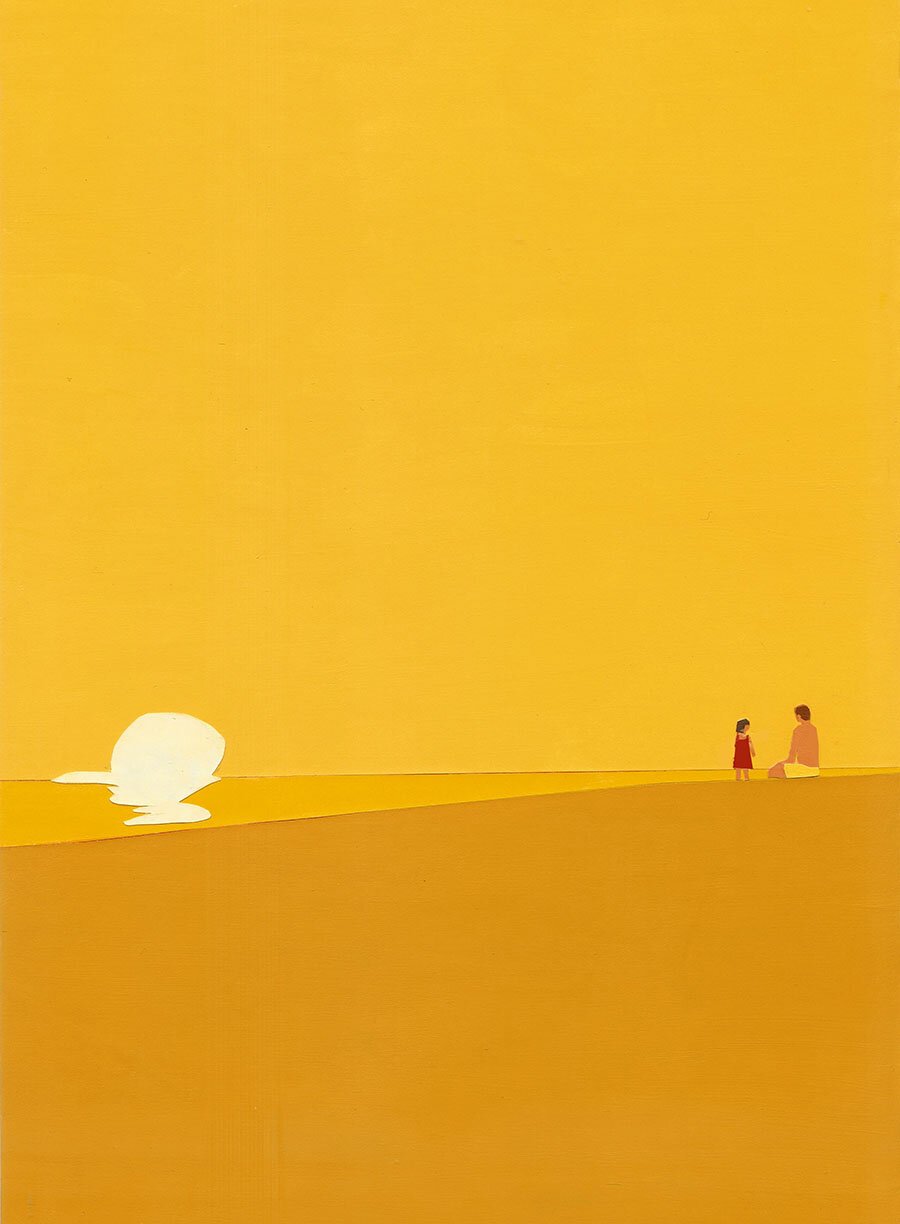

Desperate, the man cried out one last time. Beside the road, the sea churned beneath the setting sun, a rippling display of orange and blue. Within it lay the Spirit of the Ocean. A titanic koi fish fixed a midnight black eye on the man.

“Help me,” whispered the man, feeling his life’s blood seep out onto the dirt.

The spirit swam in a circle, a blotch of red and pearl paint in the water.

“I sense… my siblings have been here.” The koi’s voice resounded in the man’s mind, clear and cool like a mountain spring. “I do not have my brother’s eyes, nor my sister’s nose, but I can taste their disdain for you in the air.”

“I…” the man gasped out an answer. “I lost my inheritance. Gambled it away. My friends left me after I borrowed money I could not repay. The robbers took what little I had left.”

The spirit continued to swim, saying nothing.

“I was on … my way home to my father’s house.” The man’s breathing slowed, his chest now barely moving. “I wish I could see him one last time.”

The spirit slowed.

“I miss my siblings too,” the spirit finally replied. “I have not seen them in so long. They are too proud to dive beneath the waves and I cannot go to them.”

The man didn’t reply. His eyes closed, his expression peaceful, he at last lay still.

“The waters of the sea are mine,” said the spirit. “Let them wash you pure and restore you to new life.” Then, whipping its body in a single fluid motion, the great koi sent a wave of azure over the road. When it receded, the road was empty. Beneath the sky, between the forests and the seas, there was no sound save for the waves that caressed the pearly sands, which glistened like jewels beneath the night sky.”

***

The lights between the jester’s fingers faded like the sparkles of a firework, dissolving into individual motes of light.

“I don’t understand,” Teo-Jin said. “Did he survive?”

“That’s entirely up to you, young princeling.” The jester flourished his hands, bowed deeply, and sat on the bench. “An artist begins the work, but it is completed in the mind of the audience. The details, the meaning, what happens after—a storyteller may plant the seeds, but they flower in the imagination of the audience.”

“Absolutely not,” Teo-jin said, jabbing a figure accusingly. “You picked that story for a reason. Entranced me with that display. Does this have something to do with me and Shae-Lun?”

The jester folded his hands and smiled as he looked over the city. In the distance, dual crimson orbs touched the horizon, painting a vista of cool teal and fiery orange.

“Does a story need a reason to be told? Can it not simply live, as all things deserve? A tale is like a tapestry packed away, waiting to be unfurled and admired. And a good story leaves you with more questions, which are themselves a kind of answer.”

Teo-jin’s brow furrowed. “Fine. Let’s say he was saved. So what? What am I to learn? Tenderness?”

“The word you’re looking for, my linguistically limited lackwit, is empathy.”

“Pity is comfortable,” sighed the storyteller. “It requires little insight or perspective. This world, Teo-jin, is full of bystanders. They sit, their hearts filled with compassion, yet are paralyzed by the scale of the problem, or consumed by the challenges of their own lives, or bleed so much emotion, their hearts burst from the effort.”

“I hated them for that once. Now I understand better. It is the curse of growing old. When we are young, we yearn to do what is right, but then we find it becomes much more difficult as we age. We learn what it’s like to have a heart divided, one half wanting to make things right, one part apathetic. Is it wrong to do nothing? Absolutely. But then you learn what it is to be overwhelmed, emotionally exhausted, wrung out like an old dishcloth. And you suddenly find that compassion is hard to fit into the emotional schedule. And so sympathy ripens, spoils, and ferments into guilt, stowed away in the cellar of the body.”

“Where’s that?”

“Usually the liver.”

The boy and the storyteller sat side-by-side for a long moment, gazing toward the rolling mountains and clouds.

“So … if not because it was sorry for him, why did the koi help the man? ”

“I didn’t say that. I said that pity is an easy emotion. It comes to us like rain but leaves just as swiftly, washing off our skin. Empathy … it wells up from within. Like an underground hot spring, we feel in its warmth a connection to someone else.”

“Like the spirit in the story,” said the boy. “It knew what it was like to be alone, cast out.”

“You’d be wrong for thinking pity isn’t a powerful emotion. It often just isn’t sufficiently powerful. It is easy to ignore. Empathy is not. Empathy is looking into the eyes of a starving child and seeing your reflection. It is the whispered voice in the night, asking us what we would have wanted someone to do. It is an emotion potent enough to prod us out of our chairs, wreck our carefully ordered lives, and make us say ‘I am going to do something about this.’”

The boy sat perplexed, his brow furrowed in confusion. “I understand, I think. But, I can barely get through my days now with how others treat me!”

The storyteller slowly stood up, his knees cracking, and extended a hand. Hesitantly, the boy took it and rose to his feet. Strangely, Teo-Jin felt older. Taller. More whole.

“Are you the one who needs empathy, Teo-Jin, son of Te-Hyung? Or are you the one who can extend it?”

Teo-Jin fell silent.

“Why do you think that the others pick on you? Is it just because of Shae-Lun? Or is it perhaps that your father is favored by the emperor over all of their parents and you are a constant reminder of that fact? That both your stations and theirs were largely decided at birth? As for the princess, couldn’t it be that she is trying to live up to her own heritage, her own burden? That maybe she yearns to prove that all which will be given to her is not due to inheritance but merit?”

“None of those reasons excuse their behavior,” Teo-Jin said.

The storyteller clapped Teo-Jin on his shoulder. “Does it matter, in the end?”

“No,” Teo-Jin replied hesitantly. “It isn’t one or the other, is it—whether to be the man or the koi? I can feel hurt by them and still try to understand them.”

The storyteller smiled. “It’s your story, Teo-Jin. Your ending.”